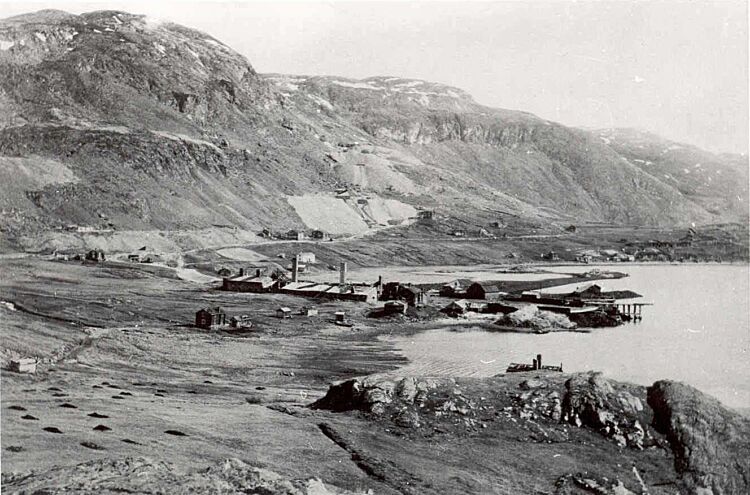

Kåfjord – the town which disappeared together with its copper resources

10 km south-west of Alta Museum and Hjemmeluft lies Kåfjord, a little side branch furthest in the Altafjord. Throughout history it has been the scene of many important events, such as the establishment of copper works in 1826. The mine had sources of power nearby for the production processes and an ice-free harbour to ship the products out to the market. The first phase with English owners lasted for 52 years (1826-1878). After that the mines lay abandoned for eighteen years. In the final production phase, the mine was managed with Swedish capital and leadership.

The ore from the Kåfjord mines had a higher copper content than those in Cornwall and Røros. It was extracted with the help of iron bores and gunpowder. The gunpowder was used to blast out horizontal shafts at different levels in the steep hillsides. The ore was carted out and piled outside the entrances. Here it was broken up by women and children. Then it was transported to a crushing plant along a double track railway line. From other shafts the ore was simply thrown down the mountain side. In the stamp mill the ore was crushed. In time a separator was introduced and a smelting plant which changed the ore into copper bars. The slag from the melting process was moulded into square bricks and used for building. Traces of the buildings and the activity around can still be seen along the 1,2 km long culture trail in Kåfjord. The clearest traces are the ruins of the ore refinery and the slagheaps.

Copper ore was also extracted at Raipas and Kvænangen and transported to Kåfjord. For a while the Raipas mine was the most profitable.

The Kåfjord mines created the basis for new livelihoods and lifestyles, and the conditions needed for a modern community. In 1840 it was the largest town in Finnmark. The leaders and owners wanted a stable and loyal workforce, but they also wanted as many as possible of those living in the mining community to be involved in the production processes. In order to achieve this they established welfare measures and benefits which never before had existed in Finnmark - sickness and disability pensions, provisions for the poor, a school, church, health care, doctor, shop, bakery, cafeteria, cultural events and homes for the workers.

It was difficult to recruit qualified workers locally in the early days of the mine. Experienced miners were employed from England, Germany and southern Scandinavia and unskilled workers from our Nordic neighbours were also welcomed into the workforce. Years with crop failures in the Torneå district of northern Sweden led to many families of Finnish descent moving to Kåfjord. A miner with a family was regarded as more stable than a single man. Paternalistic ideas, or the "fatherly care" of the owners, characterised the Kåfjord community. The leadership not only presided over the production, appointments and dismissals, but also over most aspects of the mining families' lives. They were overseen from the cradle to the grave.

Those who had settled in Kåfjord found other sources of income. A combination of agriculture, animal farming, hunting in the polar seas, the production of dried cod, salmon fishing and slate mining were the main livelihoods in Alta for the next decades. Others left Alta, moved to the coast, or emigrated across the Atlantic to America.The scorched-earth tactic of Finnmark in the autumn of 1944 destroyed the buildings. Only the church was spared.

You can learn more about the mining in Kåfjord in our permanent exhibition at Alta Museum.